Microfacet Theory - Physically Based Rendering

Roughness Using Microfacet Theory - PBRT

引入

物体在宏观上有一个法线$n$,而由于真实的表面都是坑洼不平的,对于微观的一束光,其会命中表面的一个倾斜的片(微表面)而反射出去,这个倾斜面片的法线往往和宏观的$n$方向不同。对于同一个表面从大量的光的统计上来看,越粗糙偏离的也就越大。

当然,如果我们有一个非常强悍的机器,我们可以做一个分辨率很高的模型,其表面具有真正坑坑洼洼的三角形,但是这样做时间、空间的效率都很差。

有意思的是,大量的微表面可以在统计学意义上被建模,从而让基于微表面理论的BSDF不用再受制于上面提到的问题。

光学模型

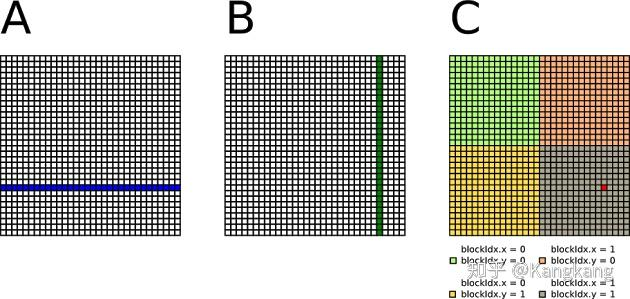

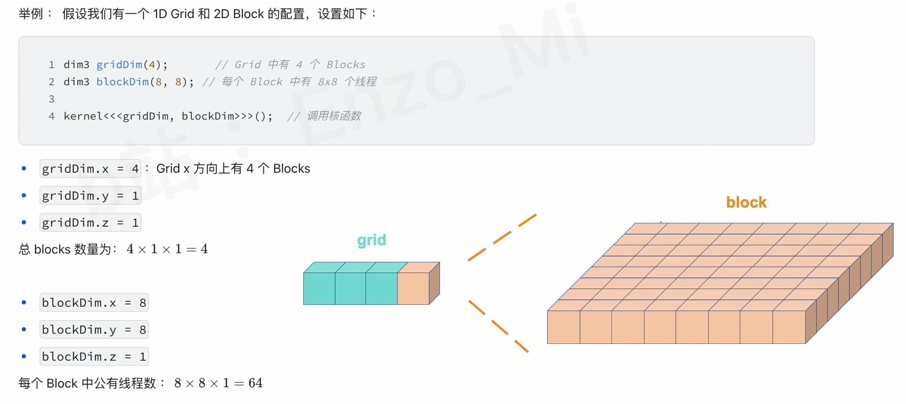

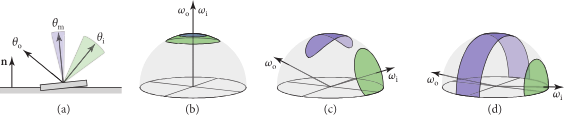

图片展示了三种光学行为

(a): 遮挡,相机看不到被照亮的地方,被其他的微平面挡住了

(b): 阴影,相机看到的地方没有光的照射,因为光线被其他的微平面挡住了

(c): 来回反射(Interreflection), 光线在微表面之间反射,最终能被相机看到

广泛使用的微表面 BSDFs 忽略来回反射。其主要由两个部分组成,一是微表面朝向的统计分布,二是描述光线如何从单个微表面散射的 BSDF

假设光源和观察者相对于微表面的尺度而言足够远的前提下,精确的表面轮廓(那些微表面的具体形状)对于遮蔽和阴影的影响相对较小。

数学推导

微表面分布项 $D(\omega_m)$

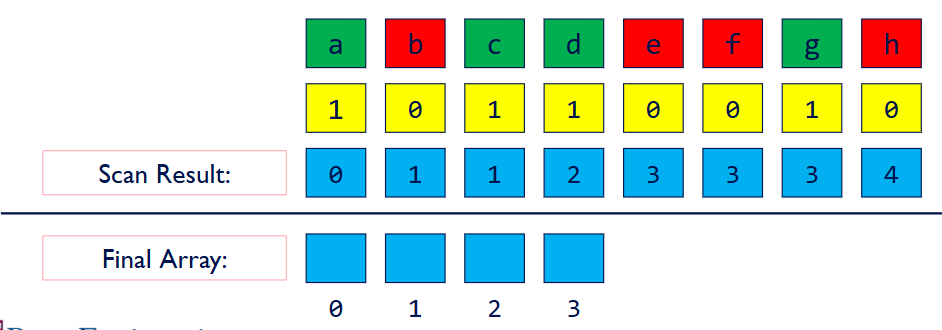

我们先不考虑遮挡和阴影,我们首先讨论法线和粗糙度的关系,而我们需要知道有多少比例的微观法线指向了某个特定方向。

我们定义$D(\omega_m)$给出的是法线朝向为 $\omega_m$ 的微表面 (microfacets) 的相对微分面积,给 $D$ 一个方向($\omega_m$),它会告诉你“有多少(宏观面积一个 $dA$中的)微观法线正指向这个方向”

所有到达 $dA$ 这个小区域的入射光线($\omega_i$)都是互相平行的。

所有离开 $dA$ 这个小区域的出射光线($\omega_o$)也都是互相平行的

其有如下关系:

$\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) (\omega_m \cdot \bold{n}) d\omega_m = \int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) \cos \theta_m d\omega_m = 1$

表示一块粗糙的表面,无论它内部多么凹凸不平,它在宏观世界(比如被太阳光照射)的总‘占地面积’是不会变的。

注意,这里的 $\bold{n}$ 在标准反射坐标系(standard reflection coordinate system)下,有 $\bold{n} = (0,0,1)$, 那么 $\omega_m \cdot \bold{n}$ 等价于 $\cos \theta_m$

$\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) \cos \theta_m d\omega_m = 1$

- $\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} \dots d\omega_m$ 检查所有($\int$)可能的倾斜方向($d\omega_m$)

- $D(\omega_m)$ 朝向 $\omega_m$ 这个方向的微表面占比是多少

- $\theta_m$ 是微表面的法线 $\omega_m$ 和“底座”法线 $\bold{n}$(垂直向上)的夹角 $\cos \theta_m$ 描述了其(投影在宏观上的)投影的面积

- $D(\omega_m) \times \cos \theta_m$ 表示所有朝向 $\omega_m$ 的木片,它们在平坦底座上的‘投影’总面积

- $\int \dots = 1$ 表示所有投影面积的总和,必须等于 1

最常见的微表面分布类型是各向同性的 (isotropic),这也会导出一个各向同性的聚合 BSDF。

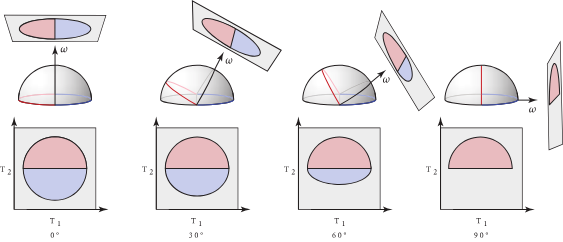

回想一下,当表面绕着宏观表面法线旋转时,一个各向同性的 BSDF 其局部的散射特性是不会改变的

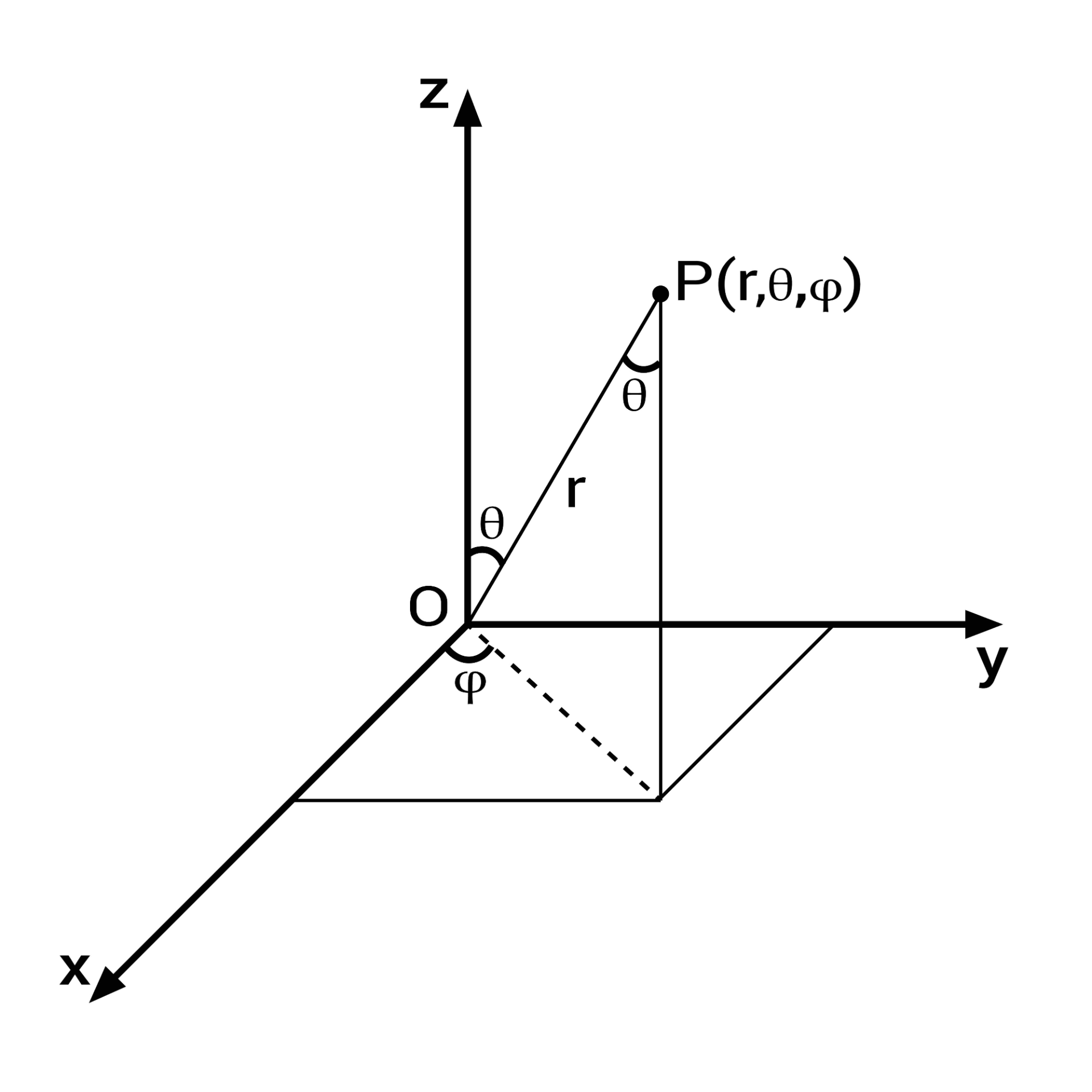

在各向同性的情况下,使用球坐标参数 $\omega_m = (\theta_m, \phi_m)$ 会得到一个只依赖于仰角 $\theta_m$ 的分布。

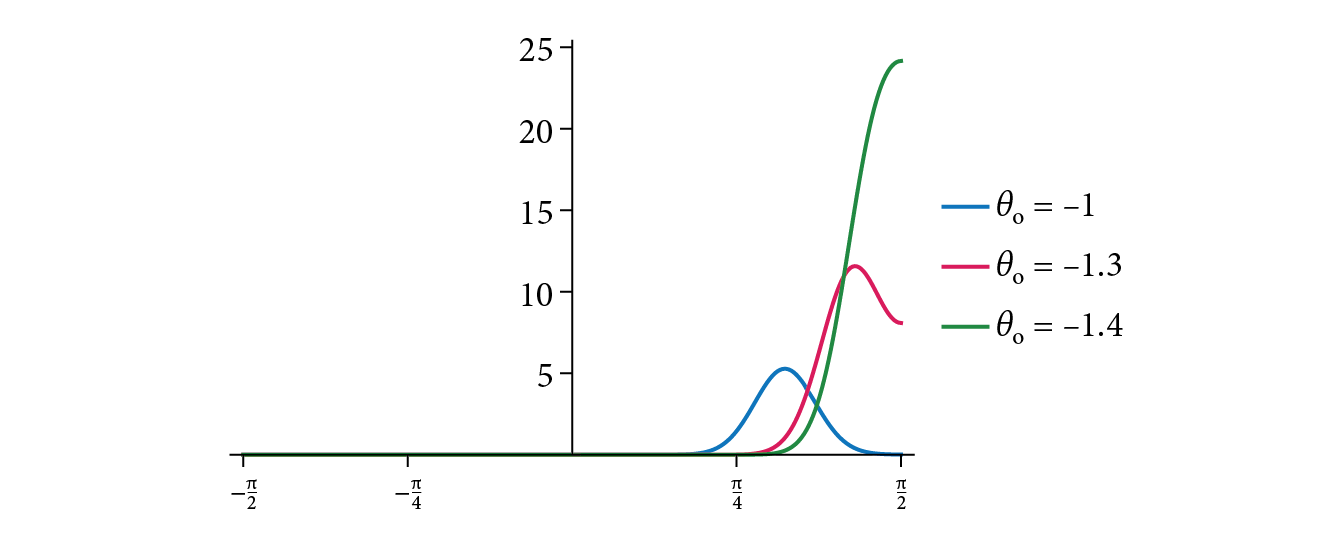

X 轴 ($\theta_m$): 微观法线的倾斜角度

Y 轴 ($D(\omega_m)$): 法线的数量(密度)

“长尾”(来自 $\theta_m$ 很大的法线)会捕捉到光,并将其散射开,形成一个非常宽广、非常柔和的“朦胧光晕”

具体实现

那么我们怎么具体去实现D的分布呢?不同的论文有不同的实现,目前比较主流的是GGX与 Disney 实现。

注意,在 D F G 三项中,一般F是通用的,而D与G项配对使用

GGX中的$D(\omega_m)$

$D(\omega_m) = \frac{1}{\pi \alpha_x \alpha_y \cos^4 \theta_m \left( 1 + \tan^2 \theta_m \left( \frac{\cos^2 \phi_m}{\alpha_x^2} + \frac{\sin^2 \phi_m}{\alpha_y^2} \right) \right)^2}$

其中,

- $\omega_m$ 是微观法线方向

- $\theta_m$ 是微观法线 $\omega_m$ 与宏观法线 $\bold{n}$ 之间的仰角

- $\phi_m$ 是微观法线 $\omega_m$ 绕着宏观法线 $\bold{n}$ 旋转的方位角

- $\alpha_x$ 和 $\alpha_y$ 是分别控制两个切线方向(x 和 y)的粗糙度参数

可以看出,$\alpha_x$ 和 $\alpha_y$ 这两个是属于材质的参数。

三种情况

$\alpha_u = \alpha_v = 0$ (完美光滑)

- $1/\alpha_u$ 和 $1/\alpha_v$ 都是无限大。

- 这意味着那个椭球体在 U 和 V 两个方向上被无限拉伸。

- 一个被无限拉伸的球体是什么?就是一个无限平坦的平面。

- 结果: 完美镜面反射。

$\alpha_u = \alpha_v$ (各向同性 / Isotropic)

- U 方向的粗糙度和 V 方向的粗糙度相等。

- 微观椭球体被均匀拉伸,变成了球形或“煎饼”形。

- 结果: 这是一个均匀粗糙的表面,比如磨砂塑料。你绕着法线旋转它,高光不会变。这就是“方位角依赖性消失了”的意思。

$\alpha_u \neq \alpha_v$ (各向异性 / Anisotropic)

- U 方向的粗糙度和 V 方向的粗糙度不相等。

- 例如,$\alpha_u = 0.5$ 但 $\alpha_v = 0.1$。

- 这意味着椭球体在 U 方向上“比较粗糙”(没怎么拉伸),但在 V 方向上“比较光滑”(被拉伸得很多)。

- 结果: 这就是“雪茄”形,它在微观上形成了“凹槽”。这就是有方向的粗糙,比如拉丝金属或木纹

特性

GGX 模型正确地指出:即使在粗糙的表面上,也存在着大量非常倾斜($\theta_m$ 很大)的微观法线

核心的高光(来自 $\theta_m$ 较小的法线)依然明亮且集中

“长尾”(来自 $\theta_m$ 很大的法线)捕捉到的光,会向四周散射,形成一个非常宽广、非常柔和的“朦胧光晕”

遮蔽项 The Masking Function $G_1(\omega, \omega_m)$

仅有 D 项的话是做不到能量守恒的 BSDF 的。因为从一个特定角度看的时候,不是所有的法线面向这个角度的微平面的面积都会被看到,我们必须避免非物理的能量引入。

我们定义 $G_1(\omega, \omega_m)$,它是一个可见度百分比(一个 0 到 1 之间的折扣因子)

对于所有朝向 $\omega_m$ 的微观法线,当我们从 $\omega$ 方向(可能是观察者方向 $\omega_o$,也可能是光源方向 $\omega_i$)去看它们时,有多少百分比 (fraction) 是没有被挡住的?

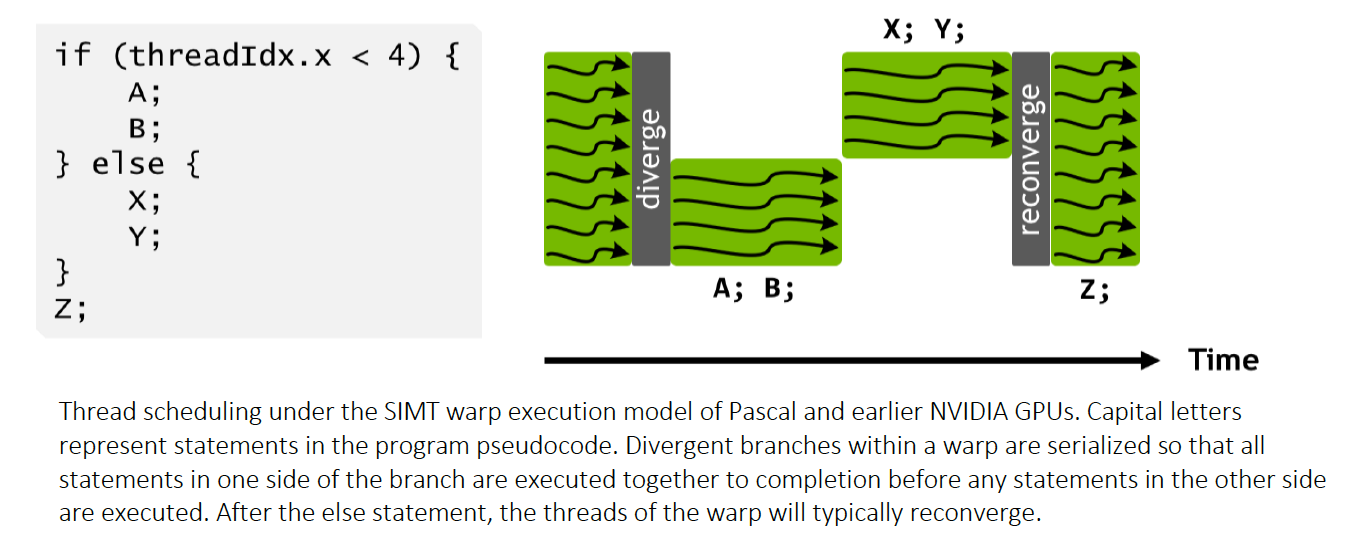

$D$ 无法确定 $G_1$ 因为我们无法知道$D$ 给出的法线分布是如何排列的,比如情况 A: 所有的 60° 陡坡都聚集在一起,形成了一面巨大的悬崖。这会投下巨大的阴影。($G_1$ 会很小)。情况 B: 所有的 60° 陡坡都均匀地、零散地分布在平地中。这只会投下很小的阴影。($G_1$ 会比较大)

为了便于计算,我们假设是情况B,也就是Smith近似。

$G_1 = 1$ 意味着百分百可见,而$G_1 = 0$意味着0% 可见

从观察者或光源的角度看,表面上的一个微分区域 $dA$ 所呈现的投影面积 (projected area) 为 $dA \cos \theta$,其中 $\theta$ 是该(观察/入射)方向与表面法线 $\bold{n}$ 之间的夹角。

(所有)可见微观表面(图中的粗线)的投影表面积加起来,也必须等于 $dA \cos \theta$。遮蔽函数 $G_1$ 给出的就是 $dA$ 上方总微观表面面积中,在给定方向上可见的比例

数学推导

$\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) G_1(\omega, \omega_m) \max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m) d\omega_m = \omega \cdot \bold{n} = \cos \theta$

$\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} \dots d\omega_m$ 检查所有($\int$)可能的倾斜方向($d\omega_m$)

$D(\omega_m)$ 朝向 $\omega_m$ 这个方向的微表面占比是多少

$\omega$ 表示想用来测试这个表面的方向

$G_1(\omega, \omega_m)$ 在所有法线朝向 $\omega_m$ 的微表面中,当我们从方向 $\omega$(比如相机方向)看过去时,有多少比例 (fraction) 是没有被其他微表面挡住的

$\max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m)$ 既负责剔除也负责投影

- 剔除 (Culling): $\omega \cdot \omega_m$ 是观察方向 $\omega$ 和微观法线 $\omega_m$ 的点积。如果这个值小于 0(即 $\omega_m$ 背向 $\omega$),$\max(0, \dots)$ 会强制将它变为 0,因为它无论如何都不可见

- 投影 (Projection): 如果这个值大于 0($\omega_m$ 面向 $\omega$),这个点积(即 $\cos \theta_{\omega, \omega_m}$)本身就是一个投影因子。它计算的是这个微观表面 $\omega_m$ 在垂直于 $\omega$ 方向的平面上的“剪影”面积

在上述的公式中,$G_1(\omega, \omega_m)$ 依赖于积分变量$\omega_m$, 而当我们做了 Smith 假设(高度和法线在统计上是独立的)之后,$G_1$ 将不再依赖于它自己的围观法线,其将只依赖于观察方向$\omega$和表面的整体粗糙度。也就是

$$

G_1(\omega, \omega_m) \approx G_1(\omega)

$$

从而,我们得到:

$$

\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) G_1(\omega) \max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m) d\omega_m = \cos \theta

$$

也就是

$$

G_1(\omega) = \frac{\cos \theta}{\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) \max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m) d\omega_m}

$$

虽然上式有解析解,但是为了简便,我们引入坡度域的辅助函数:

$$

G_1(\omega) = \frac{1}{1 + \Lambda(\omega)}

$$

$\Lambda$ 函数(我们之前用它来算 $G_1$)本身就代表了从一个方向看的“不可见”程度

$$

\Lambda(\omega) = \frac{\sqrt{1 + \alpha^2 \tan^2 \theta} - 1}{2}

$$

其中

$$

\alpha = \sqrt{\alpha_x^2 \cos^2 \phi + \alpha_y^2 \sin^2 \phi}

$$

The Masking-Shadowing Function $G$

BSDF 是一个有两个方向参数($\omega_i$ 和 $\omega_o$)的函数,并且每个方向都受到表面微观结构引起的遮挡效应的影响。

对于观察方向 ($\omega_o$) 和光照方向 ($\omega_i$),这些(遮挡效应)分别被称为遮蔽 (masking) 和阴影 (shadowing)

为了同时处理这两种情况,(单个方向的)遮蔽函数 $G_1$ 必须被推广为一个遮蔽-阴影函数 (masking-shadowing function) $G_2$,它($G_2$)给出的是(某个)微分区域中,同时 (simultaneously) 从 $\omega_i$ 和 $\omega_o$ 两个方向都可见的微表面的比例 (fraction)

如果我们假设遮蔽 (masking) 和阴影 (shadowing) 是统计上独立的 (statistically independent) 事件,那么这两个概率就可以简单地相乘:

$$

G_2(\omega_i, \omega_o) = G_1(\omega_i) G_1(\omega_o)

$$

这种假设将会刚高估阴影和遮蔽的实际数量,会导致在最终渲染的图片上出现暗区。因为这两个事件其实在统计学上并不是独立的,而是相关的。一个微表面要么倾向于对“两边”都可见,要么倾向于对“两边”都不可见。 它高估了“一个可见的表面又恰好被另一个挡住”的概率。它错误地把两个 80% 乘在了一起(得到了 64%),而真实的“同时可见”比例($G_2$)可能要高得多(比如 75%)

为了修复这个问题,我们引入新公式

$$

G_2 = \frac{1}{1 + \Lambda(\omega_i) + \Lambda(\omega_o)}

$$

- 它不再是“概率相乘”($G_1 \times G_1$)

- 它变成了“不可见量相加”

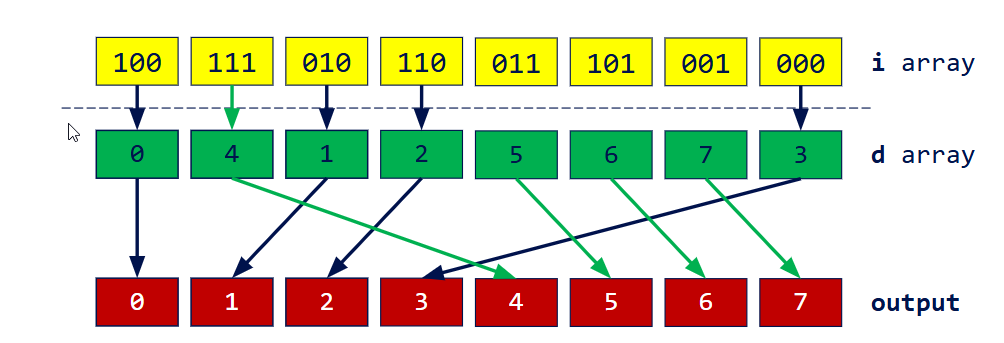

采样

现在我们考虑当一条光线从 $\omega_i$ 方向射入一个粗糙表面时,它接下来应该‘弹’向哪个随机的方向 $\omega_o$

光线会“弹”向哪里,取决于它击中了哪一个微观法线 $\omega_m$

它不能用一个“公平的”骰子(比如在所有方向上均匀抽样),因为我们知道,击中某些 $\omega_m$(比如那些正对着它的)的概率要高得多

一条光线与某个特定微表面相互作用的概率,是与它的可见面积 (visible area) 成正比的。换句话说,一束光(或视线)击中某个微表面的概率,正比于那个微表面向它呈现的可见投影面积

原公式(确保所有“可见”微表面投影的总面积是 $\cos \theta$ * $dA$)

$$

\int_{H^2(\bold{n})} D(\omega_m) G_1(\omega) \max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m) d\omega_m = \cos \theta

$$

这是所有法线朝向 $\omega_m$(附近 $d\omega_m$ 范围内)的可见微表面,它们所贡献的投影面积总和:

$$

D(\omega_m) G_1(\omega) \max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m) d\omega_m

$$

当一束光(或我们的视线)从方向 $\omega$ 射向这块表面时,它击中一个法线朝向为 $\omega_m$ 的微表面的(法线空间)概率是多少?:

$$

D_\omega(\omega_m) = \frac{G_1(\omega) D(\omega_m) \max(0, \omega \cdot \omega_m)}{\cos \theta} \quad

$$

$$

D_\omega(\omega_m) = \frac{\text{朝向 }\omega_m\text{ 的可见投影面积}}{\text{所有可见投影面积的总和}}

$$

也就是我们给$D$一个向量,其会返回 $\omega_m$ 被击中的概率是 $X$

而Sample() (采样算法)是“骰子”

- 作用这是一个生成函数。

- 输入: 它通常只需要 1 或 2 个 0 到 1 之间的随机数(比如 rand(), rand())。

- 输出: 它“吐出”一个全新的、随机的向量 $\omega_m$(“这是我帮你‘摇’出来的方向!”)。

那么如果说完全随机地去得到方向,最后调用$D_{\omega}(\omega_m)$来事后告诉我们这个随机 $\omega_m$ 的概率是 $0.0001%$,这个渲染器是可以工作的,但是十分低效。

我们需要重要性采样,我们在得到方向地时候,这个随机方向的产生器就要产生更多的高概率方向,而较少地产生低概率方向。

那么如何制作这样的采样器呢?有数学上的方法,但是有一个相对简单的几何途径可以做到。

几何方法(可见法线采样)

- 在代码中,假想一个由粗糙度 $\alpha_x, \alpha_y$ 定义的标准GGX椭球体

- 计算这个“椭球体”从方向 $\omega$ 看过去的2D剪影 (2D silhouette)

- 在这个2D剪影上,均匀地 (uniformly) 随机选择一个 2D 点 $(u, v)$

- 从这个 2D 点 $(u, v)$,沿着 $\omega$ 方向“逆向”投射回3D椭球体上,找到那个唯一的撞击点 $p$

- 获取这个 3D 撞击点 $p$ 在椭球体上的表面法线 $\omega_m$

- 这个方法已经处理了遮蔽

微观“凸起”的 2D 剪影的形状,会根据你的“观察角度 $\omega$”而改变。这个算法必须精确地模拟这个改变

The Torrance–Sparrow Model

给定一个来自方向 $\omega$ 的观察光线,我们使用‘可见法线采样’(“骰子”),从**可见法线分布$D_\omega(\omega_m)$(“裁判”)所定义的概率中,生成 (sample) 一个微观法线 $\omega_m$**。并且,我们同时会使用$D_\omega(\omega_m)$ 这个公式,来计算出我们刚刚生成的那个 $\omega_m$ 所对应的概率密度值(一个数字/Float)

- 这一步(在概念上)封装了“观察光线”与“随机的微观结构”求交 (intersecting) 的过程

- 注意,这一步产生的$\omega_m$可能会相对于原宏观$\bold{n}$偏离很大,从而导致从一些角度射进来的光线,会被反射到V型谷的深处,而非去向摄像机,然后也许会经历多次反弹,最终射向摄像机。但是,Smith’s GGX的数学模型没有包括这种情形,导致了能量损失,其较为粗略地将这样的光线终止。当材质非常粗糙的时候,这种情况将会很常见。有一些研究进行了对这种情况的不同程度的修补。如 Fast-MSX: Fast Multiple Scattering ApproximationFast-MSX

(光线)在被采样的微表面上的反射,是使用镜面反射定律 (law of specular reflection) 和菲涅尔方程 (Fresnel equations) 来建模的

- 这会(反向)推导出一个入射方向 $\omega_i$,以及一个反射系数 (reflection coefficient),该系数会衰减 (attenuates) 这条路径所携带的光

最终,散射的光会(再)乘以一个 $G_1(\omega_i)$,以计入其他微表面所造成的阴影效应

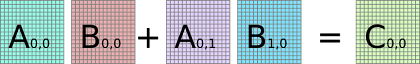

在渲染器中,我们有来自上一次光的交互带来的$\omega_o$,我们要算出$\omega_i$ 以及其对应的概率密度,并完成采样。

想象一个法线 $\omega_m$。向量 $\omega_o$ 和 $\omega_i$ 在 $\omega_m$ 的两侧对称

注意:在 PBRT 的约定中,所有向量 $\omega_i, \omega_o, \omega_m$ 都指向外

根据镜面反射关系,有:

$\omega_i = -\omega_o + 2(\omega_m \cdot \omega_o) \omega_m$

$\omega_m = \frac{\omega_i + \omega_o}{|\omega_i + \omega_o|}$

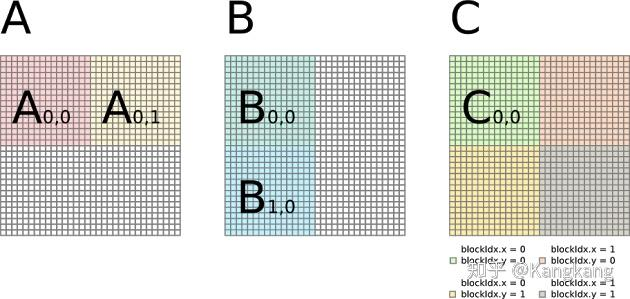

我们固定出射方向 $\omega_o$,并可视化一组微表面(用蓝色阴影表示),这些微表面能将来自入射方向(用绿色阴影表示)周围的一个弧/锥的光线有效反射出去

- 在 (a) 所示的二维平面 (flatland) 设置中,这组有效的微表面 (admissible microfacets) 只是一个更小的弧。3D 情况则更复杂,涉及到球面圆锥截面 (spherical conic sections)。

- 在 (b) 中,当 $\omega_i$ 锥体的中心与 $\omega_o$ 对齐时,有效的微表面形成一个球面圆形 (spherical circle)。

- 在 (c) 中,当 $\omega_o$ 与 $\omega_i$ 锥体中心方向之间呈 $45^{\circ}$ 角时,有效的微表面形成一个球面椭圆 (spherical ellipse)

- 在 (d) 中,当角度为 $90^{\circ}$ 时,结果则是一个球面双曲线 (spherical hyperbola)

我们想要知道最终选出的$\omega_i$的概率密度是多少,而非$\omega_m$,他们的关系是:

$p(\omega_i) d\omega_i = p(\omega_m) d\omega_m$

$p(\omega_i) = p(\omega_m) \times \frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i}$

我们先关注 $\frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i}$,其表示在 $\omega_m$ 空间中一个无限小的立体角 $d\omega_m$”,除以“在 $\omega_i$ 空间中对应的那个无限小的立体角 $d\omega_i$。

而又有,在球面坐标中,微分立体角 $d\omega = \sin\theta d\theta d\phi$

$$

\frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i} = \frac{\sin \theta_m d\theta_m d\phi_m}{\sin \theta_i d\theta_i d\phi_i}

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i} &= \frac{\sin \theta_m d\theta_m d\phi_m}{\sin (2\theta_m) (2 d\theta_m) (d\phi_m)} \

&= \frac{\sin \theta_m}{ (2 \sin \theta_m \cos \theta_m) \cdot 2} \

&= \frac{1}{4 \cos \theta_m} \

&= \frac{1}{4(\omega_i \cdot \omega_m)} = \frac{1}{4(\omega_o \cdot \omega_m)}

\end{aligned} \quad

$$

也就是

$$

p(\omega_i) = D_\omega(\omega_m) \times \frac{1}{4(\omega_o \cdot \omega_m)}

$$

BSDF

evaluate 公式的推导:

回顾一下渲染方程:

$L_o(\text{p}, \omega_o) = \int_{H^2(\mathbf{n})} f_r(\text{p}, \omega_o, \omega_i) L_i(\text{p}, \omega_i) |\cos \theta_i| d\omega_i$

单样本蒙特卡洛估计器:

$$

\approx \frac{f_r(\text{p}, \omega_o, \omega_i) L_i(\text{p}, \omega_i) |\cos \theta_i|}{p(\omega_i)}

$$

结合在一起,有

$$

\begin{aligned}

L_o(\text{p}, \omega_o) &= \int_{H^2(\mathbf{n})} f_r(\text{p}, \omega_o, \omega_i) L_i(\text{p}, \omega_i) |\cos \theta_i| d\omega_i \

&\approx \frac{f_r(\text{p}, \omega_o, \omega_i) L_i(\text{p}, \omega_i) |\cos \theta_i|}{p(\omega_i)}

\end{aligned}

$$

Torrance–Sparrow 模型给出的单光线的辐射亮度,应该和蒙特卡洛估计相一致:

$$

\frac{f_r(\text{p}, \omega_o, \omega_i) L_i(\text{p}, \omega_i) |\cos \theta_i|}{p(\omega_i)} \stackrel{!}{=} F(\omega_o \cdot \omega_m \text{(反射角度)}) G_1(\omega_i) L_i(\text{p}, \omega_i)

$$

把两边的 $L_i$ 消掉,有

$$

\frac{f_r \cdot |\cos \theta_i|}{p(\omega_i)} = F(\omega_o \cdot \omega_m) G_1(\omega_i)

$$

移项,有

$$

f_r = \frac{F \cdot G_1(\omega_i) \cdot p(\omega_i)}{|\cos \theta_i|}

$$

代入 $p(\omega_i)$,有

$$

p(\omega_i) = p(\omega_m) \times \frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i}

$$

而$p(\omega_m)$是:

$$

p(\omega_m) = D_\omega(\omega_m) = \frac{G_1(\omega_o) D(\omega_m) (\omega_o \cdot \omega_m)}{(\mathbf{n} \cdot \omega_o)}

$$

$\frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i}$ 是:

$\frac{d\omega_m}{d\omega_i} = \frac{1}{4 (\omega_o \cdot \omega_m)}$

则有:

$$

p(\omega_i) = \frac{G_1(\omega_o) D(\omega_m)}{4 (\mathbf{n} \cdot \omega_o)}

$$

则有:

$$

f_r = \frac{F(\omega_o \cdot \omega_m) \cdot G_1(\omega_i) \cdot p(\omega_i)}{(\mathbf{n} \cdot \omega_i)}

$$

则有:

$$

f_r = \frac{F(\omega_o \cdot \omega_m) \cdot G_1(\omega_i) \cdot \left[ \frac{G_1(\omega_o) D(\omega_m)}{4 (\mathbf{n} \cdot \omega_o)} \right]}{(\mathbf{n} \cdot \omega_i)}

$$

然而,这个 $G = G_1 \times G_1$ 的“非相关”几何项会导致渲染过暗。因此,在最终的实现中,我们将其替换为物理上更精确的“高度相关”模型 $G_2 = \frac{1}{1 + \Lambda(\omega_i) + \Lambda(\omega_o)}$